Will local energy change electricity bills?

ENERGYTRANSFORMATIONRESENERGY COOPERATIVESENERGY COMMUNITY

Poland’s Path Toward Citizen Energy

Building on the topics introduced in the first part of this article ("How energy cooperatives are changing the rules of the game in Poland’s energy market?"), the present publication focuses on the practical and evidence-based aspects of how energy cooperatives operate. Its aim is to test the assumptions of the theoretical model using real-world data and case analyses.

The analysis covers the dynamics of the sector’s development in Poland between 2021 and 2025, a comparison with the mature German model, modelling of potential savings based on a case study, and an overview of implementation procedures and available financial instruments.

The Development of Energy Cooperatives in Poland and a Case from Abroad

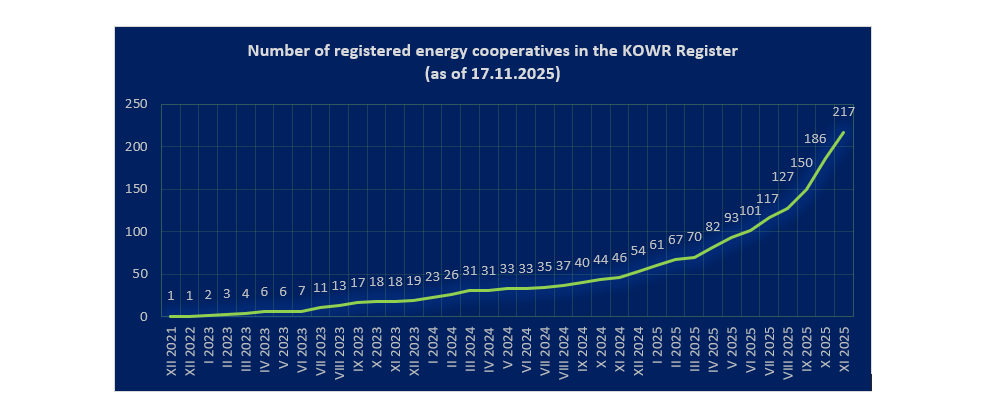

The energy cooperative sector in Poland has been growing rapidly, although its history remains relatively short. By the end of 2021, only a single cooperative was registered nationwide, and the figure remained unchanged a year later. A breakthrough came in 2023, when an amendment to the law expanded the definition of energy cooperatives to include non-agricultural entities. As a result, the number of registered cooperatives surged from 13 at the end of 2023 to 54 in 2024, and as many as 217 by 17 November 2025. If the current growth rate continues, the number could exceed 250 by the end of the year.

A key driver of this expansion was the reduction of the minimum self-consumption threshold from 70% to 40%. The new regulations made it possible to establish cooperatives based solely on photovoltaic installations, without the need for precise alignment between energy generation and consumption profiles or costly energy storage systems. This change has significantly simplified the process of establishing cooperatives, making it more accessible for smaller municipalities and local communities.

As of early November 2025, the largest cooperative registered in the National Support Centre for Agriculture (KOWR) operated installations with a combined capacity exceeding 6 MW. In total, across all 217 cooperatives, there are now more than 1,000 renewable installations with an aggregate capacity surpassing 95 MW. The median installed capacity per cooperative stands at around 130 kW, reflecting the dominance of small and medium-scale, community-driven projects. The highest concentration of energy cooperatives is found in the Wielkopolskie (30) and Mazowieckie (24) regions, while the lowest numbers occur in Podlaskie (3), Łódzkie and Warmińsko-Mazurskie (7).

In contrast, Germany offers a mature model of cooperative energy development, exemplified by Bürgerenergie Rhein-Sieg eG, based in Siegburg, North Rhine-Westphalia. Founded in 2011, the cooperative currently brings together around 300 members and delivers energy projects serving several hundred consumers. It operates multiple photovoltaic systems with a total capacity exceeding 1 MW, including a flagship installation on the roof of a senior center in Siegburg.

Bürgerenergie Rhein-Sieg continues to expand, planning new solar farms and renewable projects such as the Sinzig initiative, aimed at increasing installed capacity and supplying thousands of households. In the coming years, the cooperative plans to invest substantial funds in renewable energy development, reinforcing its role as one of the leading community energy actors in the Bonn and North Rhine-Westphalia region.

Case study

To illustrate how an energy cooperative operates, a simplified example of a local energy community is presented. The model assumes a cooperative operating a generation source with a capacity of approximately 1.5 MW, producing around 1,500 MWh of electricity per year, with total internal consumption of 1,700 MWh. Two self-consumption scenarios and reference energy prices were applied in the analysis: PLN 750/MWh as the internal energy price and PLN 1,200/MWh as the standard market price.

In the following analysis, the self-consumption level is defined as the share of internally generated energy in the cooperative’s total annual consumption.

In the full self-consumption scenario (i.e. when all energy produced is consumed by cooperative members at the moment of generation), the total cost of electricity amounted to PLN 1,365,000, compared with PLN 2,040,000 under standard market tariffs. This translates into a saving of approximately PLN 675,000, or around 33%.

In the limited self-consumption scenario, where 40% of the total energy demand is met by internal production, the cooperative’s total cost reached PLN 1,734,000, resulting in savings of PLN 306,000, or roughly 15% compared to market prices.

This model includes certain simplifications, it does not account for real-time consumption variability or seasonal fluctuations in energy generation. The analysis is therefore illustrative in nature and aims to demonstrate the potential economic benefits rather than their full optimization.

In practice, cooperatives rarely achieve full self-consumption based solely on a single energy source. Increasingly, hybrid models are applied, combining photovoltaics with wind installations, energy storage systems, or biogas plants. Such diversification enables better alignment between production and demand, increases self-consumption, and improves the overall economic performance of the system.

This example highlights the importance of precise planning in both energy production and consumption. It not only maximizes savings but also mitigates risks related to energy price volatility and suboptimal external contracts. It should be noted, however, that in addition to typical energy purchase and sale relations, other costs also arise, such as plant modernization, reserve funds, or ongoing management, all of which affect the cooperative’s final economic balance.

Tangible and Intangible Benefits of Energy Cooperatives

Energy cooperatives deliver benefits on three key levels: economic, environmental, and social.

Through self-consumption and partial exemption from distribution fees, cooperative members significantly reduce their energy costs, stabilize expenditures, and become less dependent on wholesale market fluctuations. Proper planning of energy generation and consumption helps maximize savings and shorten investment payback periods.

Local renewable energy sources reduce CO₂ emissions, support the energy transition, and contribute to achieving the European Union’s climate objectives. At the same time, they help improve environmental quality and strengthen the image of socially responsible organizations.

Energy cooperatives also play a vital social role, integrating local communities by involving residents in decision-making and energy management processes. They stimulate local economies, enhance resilience to energy crises, and foster social capital development. Transparent governance and collective decision-making contribute to greater civic awareness and responsibility for shared energy resources.

At the system level, energy cooperatives act as stabilizers for local electricity networks. Generating power close to the point of consumption eases the load on transmission lines and reduces network losses, an increasingly important factor amid rising grid congestion. For this reason, the development of distributed energy systems, including cooperatives, should focus on areas with real local demand for energy, close to end users. Such an approach not only increases network efficiency but also helps avoid costly investments in high-voltage transmission infrastructure.

In a broader perspective, energy cooperatives are becoming tools for rationalizing the power system. They combine economic, environmental, and social dimensions while simultaneously improving local energy security and the resilience of the overall infrastructure.

Establishing an Energy Cooperative – Step by Step

After completing an analysis of energy generation and consumption, an energy cooperative must meet a series of formal requirements. The first step is to adopt the cooperative’s statute and register it in the National Court Register (KRS). This is followed by appointing supervisory bodies, securing an energy source, and registering the cooperative in the National Support Centre for Agriculture (KOWR) database.

The next stage involves formalizing relationships between the cooperative, the electricity supplier, and the distribution system operator. Once these procedures are completed, the registration process can be considered finalized. At that point, the focus shifts to ensuring efficient and transparent energy settlements.

At every stage, it is advisable to seek professional support, from planning and designing installations, through securing financing, to ongoing management of the energy community. Technical and legal advisory services are invaluable when integrating different renewable energy sources, maximizing self-consumption, and ensuring the optimal use of cooperative mechanisms.

A Few Words on Financing

Energy cooperatives in Poland have access to various financing mechanisms that enable the rapid deployment of renewable energy sources (RES) and energy storage systems under favorable conditions. The most important programs include:

“Energy for the Countryside” Program, offered by the National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management (NFOŚiGW), this scheme targets cooperatives and their members. It provides grants and preferential loans for installations ranging from 10 kW to 10 MW, with the possibility of partial loan forgiveness (up to 25% of the capital). Support for energy storage systems can cover up to 20% of investment costs, while the maximum loan amount reaches PLN 25 million, with a five-year commitment period.

“My Electricity” Program – although primarily designed for individuals, cooperatives may also apply for funding of photovoltaic (PV) systems up to 50 kW. The program offers grants covering up to 50% of eligible costs, capped at PLN 4,000, provided the installation is connected to the grid.

Financing through BOŚ Bank (Bank Ochrony Środowiska) - the bank supports the construction, expansion, and modernization of renewable energy projects, requiring an own contribution of 10–20% of the project’s total value. Cooperative members holding accounts with BOŚ benefit from simplified settlements and enhanced financial monitoring.

EU and regional funds - additional grants and loans are available through cohesion policy funds, energy transition programs, and regional environmental funds.

Typical financing conditions include an own contribution of 10-20%, maintaining the environmental effect for at least five years, compliance with the Renewable Energy Sources Act, and adherence to relevant technical standards.

Summary

Energy cooperatives represent a practical response to the dual challenges of rising energy prices and the growing pressure of the national energy transition. Their value lies not only in the potential for significant cost savings but, above all, in introducing a new model of collaboration and energy solidarity within local communities. By joining forces, residents, businesses, and municipalities can jointly produce and consume energy, reducing exposure to central market price volatility while actively participating in the local energy transition.

Mechanisms such as self-consumption, net-metering, and the integration of multiple renewable sources make it possible to maximize both economic and environmental benefits. When properly designed, an energy cooperative also generates tangible social effects, it strengthens community ties, increases resilience to energy crises, and supports local economic development.

For those looking to start their own cooperative, careful preparation is essential, from strategic planning and source selection to legal and financial structuring. When managed properly, such a project becomes not only a source of clean energy but also a driver of local stability, cooperation, and sustainable growth.

In conclusion, energy cooperatives demonstrate that citizen energy is not just a theoretical concept, it works in practice and delivers real value, both economically and socially. The real challenge, however, begins when energy must be delivered precisely at the moment it is needed. The next article in this series will take a closer look at this issue, exploring why matching generation and consumption profiles remains one of the most complex, and fascinating aspects of modern energy communities.

Sources:

1) https://be-rhein-sieg.de/, https://buergerwerke.de/anlagen-und-begn/begn/buergerenergie-rhein-sieg-eg